MLP Language Model with JAX

Introduction

This blog post shows how to perform a natural language processing using a simple MLP and JAX. Throughout this blog post I will assume that you are familiar with my last blog post so if you didn’t read that already go and check that out here.

Going further

In the last blog post, we explored a simple bigram model where we trained a basic neural network without a hidden layer to perform the following task: given a word—or, in our case, a character—predict the next character.

Now, we will take it a step further by using multiple characters to predict the next character. We will train the model on the same data as the bigram model and compare their performances.

Another key difference is that we will use a much larger neural network. For the bigram model, we simply had one matrix with dimensions 27 by 27, where 27 was the size of our vocabulary. Now, we will find an embedding for every character, pass this through a hidden layer with a non-linear activation function, and finally output everything through a linear layer.

But lines of code say more than words, so let’s move on to the implementation part now.

Implementation

Data Loading and Preprocessing

The data loading process remains the same, as does the encoding of a word. We won’t repeat that here. If you haven’t read the last blog post, I suggest you do so at this stage.

The first difference is in how we build our dataset.

def get_dataset(encoded_words: List[List[int]], block_size: int) -> Tuple[Array, Array]:

"""

Take block size letters to predict the next letter.

"""

X = []

y = []

for word in encoded_words:

context = [0] * block_size

for token in word[1:]:

X.append(context)

y.append(token)

context = context[1:] + [token]

return jnp.array(X), jnp.array(y)

As you can see, our function now takes an additional argument called block_size, which is the number of tokens we use to predict the next token. We initialize the context, which is what we provide to the neural network to predict the next token, with zeros representing our special

To illustrate this, let’s look at a simple example of the tokenization process for the word “emma”:

<eos><eos><eos> -> e

<eos><eos>e -> m

<eos><eos>em -> m

<eos><eos>emm -> a

<eos><eos>emma -> <eos>

Above, you can see on the left side the corresponding training points and on the right side the targets for each training point.

We then proceed to divide our training set randomly into train, dev, and test sets. You can find the code for that in the repository, which I will link later. I fixed a random seed to ensure deterministic behavior.

Model

Now we come to the interesting part: the implementation of our model. Our model has the following parameters:

class MLPParams(NamedTuple):

embedding: Array

W1: Array

b1: Array

W2: Array

b2: Array

What each of these means becomes clearer when we look at the forward function.

def forward(params: MLPParams, X: Array) -> Array:

embedded = params.embedding[X] # (batch_size, block_size, embed_size)

embedded = embedded.reshape(X.shape[0], -1) # (batch_size, block_size * embed_size)

hidden = jnp.tanh(embedded.dot(params.W1) + params.b1) # (batch_size, hidden_size)

output = hidden.dot(params.W2) + params.b2 # (batch_size, vocab_size)

return output

At the first stage, we perform what is called embedding the tokens, which is essentially looking up their corresponding vectors in a lookup table. For each token, we have an embed_size-dimensional vector, and we retrieve these vectors from the embedding matrix during training. This matrix learns a meaningful representation of each token.

Next, if X has the dimensions (batch_size, block_size), as shown in the data processing part, the lookup will result in a 3D array with dimensions (batch_size, block_size, embed_size). We need to reshape this into a 2D matrix to use familiar NumPy syntax. We then multiply the resulting matrix by another matrix W1, add the bias b1, and apply a non-linear activation function, which is the hyperbolic tangent (tanh). Note that we follow the implementation from the original paper by Bengio et al., which is why we use the tanh activation function. Nowadays, it is more common to use a ReLU activation function at this stage.

The final step is to output the logits by multiplying the hidden layer’s output with the second matrix W2 and adding the bias term b2. This results in our final logits.

Our loss function is the familiar cross-entropy loss, which I described in the first blog post. The training process is also standard and can be found in the repository linked at the end of this post.

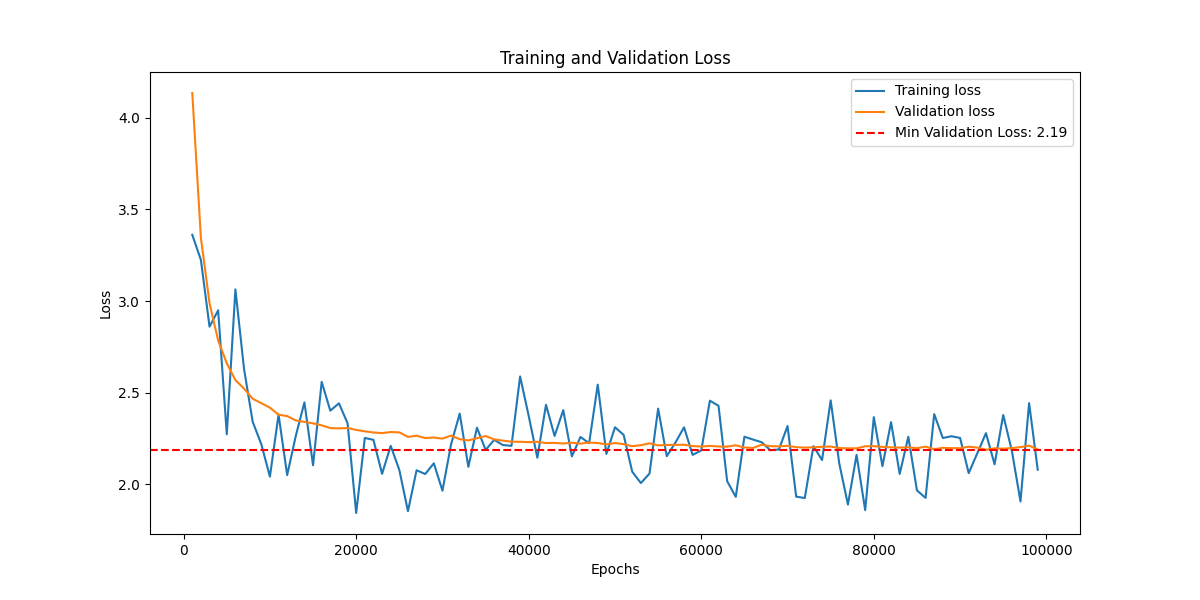

One interesting aspect is that during training, we used mini-batch training. In each epoch, we sample a small batch of the training data, use that batch to compute the gradients, and then use the resulting gradients to update our weights. This approach makes training more efficient and requires less memory. However, the training loss may not decrease as smoothly as when using the entire dataset. As we will see, this approach is sufficient here and is also a common practice in general.

Let’s look at our loss curves now. Here, I plotted both training and validation loss. The training loss doesn’t matter much if our model cannot generalize, so we should always evaluate on the holdout validation set.

This is encouraging because we see a significant improvement in performance compared to our bigram model. Additionally, we observe that the training and validation loss are roughly of the same order, indicating that we don’t overfit. The bumpy behavior in the training loss is easily explained by the use of mini-batch updates, which introduce some noise since we don’t compute the full gradient.

This is encouraging because we see a significant improvement in performance compared to our bigram model. Additionally, we observe that the training and validation loss are roughly of the same order, indicating that we don’t overfit. The bumpy behavior in the training loss is easily explained by the use of mini-batch updates, which introduce some noise since we don’t compute the full gradient.

Now, let’s move on to the sampling part. The sampling process is largely the same as before, but we need to input three encoded characters into our neural network because that’s how we trained it.

def sample(params: MLPParams, key: Array, vocab: List[str]) -> str:

"""

1) Start with <eos>

2) Index into the weights matrix W for the current character

3) Sample the next character from the distribution

4) Append the sampled character to the sampled word

5) Repeat steps 3-5 until <eos> is sampled

6) Return the sampled word

"""

current_chars = jnp.array([vocab.index("<eos>"), vocab.index("<eos>"), vocab.index("<eos>")])[

None, :

]

sampled_word = ["<eos>", "<eos>", "<eos>"]

while True:

key, subkey = jax.random.split(key)

logits = forward(params, current_chars)

sampled_char = random.categorical(subkey, logits=logits)[0]

current_chars = jnp.concatenate(

[current_chars[:, 1:], jnp.array([sampled_char])[None, :]], axis=1

)

sampled_word.append(vocab[sampled_char])

if sampled_char == vocab.index("<eos>"):

break

return "".join(sampled_word)[len("<eos><eos><eos>") : -len("<eos>")]

We can then examine the kinds of words the neural network is able to produce after training:

karmelmanie

zaaqa

tri

caurelle

raamia

carlyn

mavin

artha

jaamini

tina

These results are much better than those from the bigram model. The generated words sound more name-like. While some may not be real names, examples like tine, carlyn, and caurelle certainly sound plausible. So that’s it for now with the blog post. As before, this is heavily influenced by the lecture of Andrej Karpathy. The experiments were performed on a TPU provided by TRC research program. If you have questions or suggestions, please let me know. If you are interested in the code, you can find it at my gitub. If you have any questions, please let me know and I will try to answer them as best as I can.